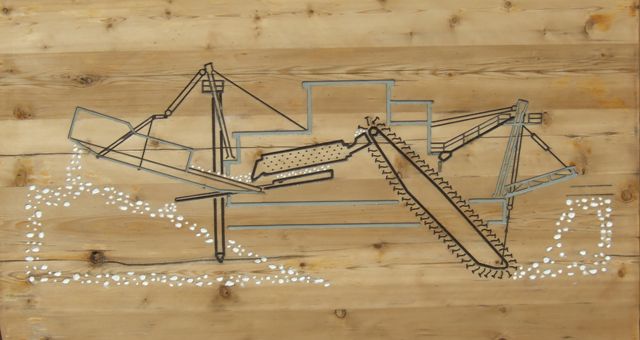

| The visitor centre in

Dawson City has a model of Gold Dredge No 4, so we went to have a look at

the real thing which was about 13km up a dirt road by the side of our

campground. |  |

|

The dredge is being restored by Parks Canada and they give guided tours. It

is seven stories high but when it was operational it was crewed by a team of only 5! |

| The gold rush

here only lasted a few years in the late 1800s with individual miners panning for gold by

hand. Each was only allowed one claim of about 500ft square.

By the early 1900s, companies were buying up the claims and

'consolidating' them. They then brought in mechanisation to work the claims.

Hence the company names such a Consolidated Goldfields. |

| The dredge sat in a pond

of water and had a chain of buckets which dug 74 feet down into the gravel.

This material

was then tipped into a hopper and progressively washed and the unwanted

gravel was deposited behind the dredge. After each sweep by the bucket

chain the dredge was moved forward 10ft. The dredge moved about half a mile

per year. |  |

|

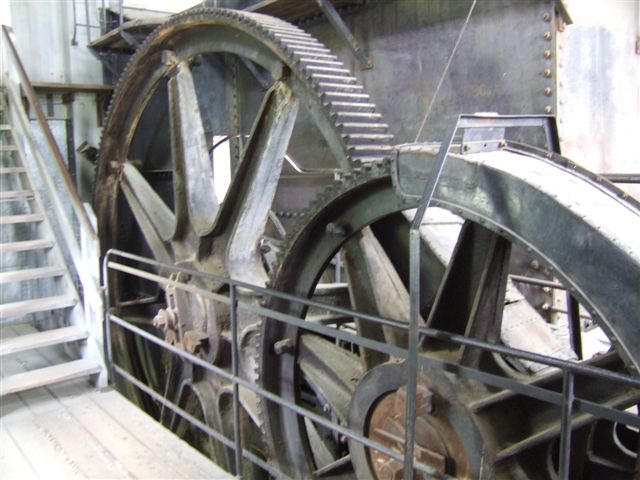

The bucket chain ran over this roller. The dredge worked 24/7 for about 250

days each year. When the ground became too cold they did maintenance over the

winter. Note the man posing just by the pulley to give some scale. |

| Inside is full of

machinery. Oddly enough it was electrically powered from a hydro-electric

scheme which also powered Dawson City. When the dredge was working hard,

the lights dimmed in Dawson. The water for the hydro scheme was brought by

channels and pipes over 75 miles - a feat comparable to the construction of

the Panama Canal. This is one of the water pumps which provided the water to

wash the gravel. Millions of gallons were needed. |  |

|

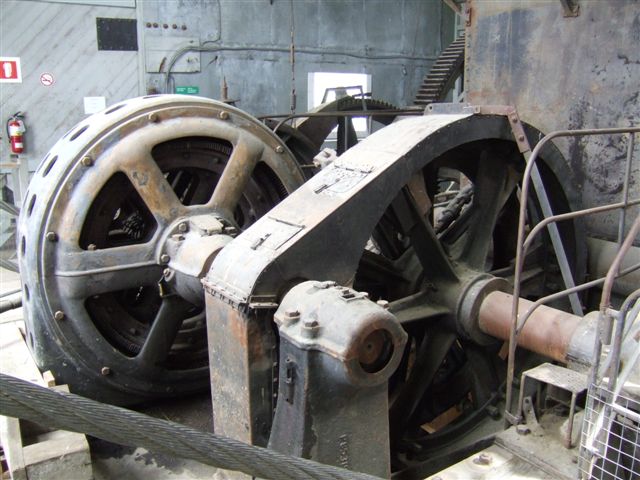

One of the winches used for moving the dredge forward via a set of cables. |

| These large gears (there

is another one on the other side) were powered

by a 300hp motor and drove the bucket chain. Most of the engineering parts

were brought in by ship to Skagway then by river boat to Whitehorse.

The two largest wouldn't fit through the railway tunnels and so came in by river from

the mouth of the Yukon River, a distance of 1800 miles. |  |

|

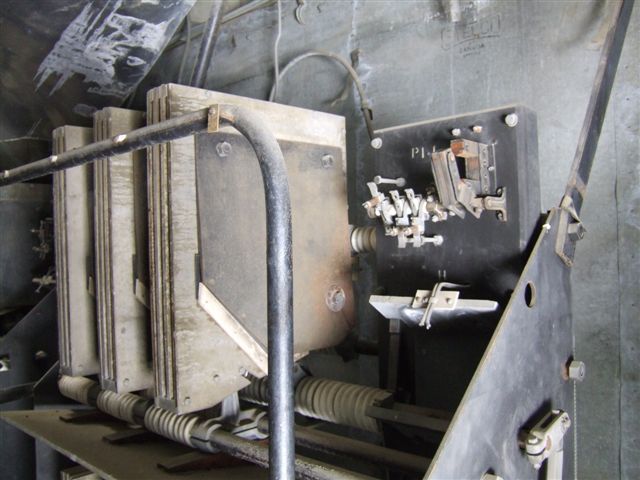

Up in the main control room there is a mass of early electrical switching

gear. The wiring was stripped out for the value of the copper long before renovation was thought about. |

| The dredge worked from

1909 until 1959 and recovered almost two million ounces of gold. It paid for

the cost of construction, and made some profit, in its first year. |  |

|

These levers controlled the winches and the brakes. They would have required

huge manual effort. |

| Part of the pond in which

the dredge sat. It moved its pond with it, excavating in front and filling

in with the spoil behind. The bucket chain was removed in

winter for maintenance. A dam collapsed in 1959 and the dredge was badly

damaged. It never worked again. By 1964 all the 20 dredges in the goldfield

had ceased operations. (Gold was then a fixed $35 an ounce. Today the price

fluctuates, now around $1200 - but

it is still not economic to restart dredging operations). |  |

|

The main 300hp motor. Most of the machinery was built in Ohio. |

| These are the sluice

channels. The excavated gravel was fed through the hopper and into a long

rotating drum with varying sized holes, sifting out the smaller pebbles. These

were decanted into

the sluices where they were constantly washed with high and low pressure

water. The tiny flakes of gold ('sugar') were 19 times heavier than the water and sank

quickly. Coir mats lined the bottom of the channels and collected the gold.

The mats were collected weekly and the gold recovered. The dredges were 90%

efficient. |  |

|

Brakes on the winches. The long rods come down from the control room levers.

There was no hydraulic support for movement. |

| The tailings passed out

the back of the dredge and filled in behind it. They left a very

characteristic pattern like a giant worm cast behind the dredges as they moved along the

valley bottoms. It would not be permitted to be left like that today. But

nature is slowly recovering and populating the spoil heaps with plants. |  |

|